We Shouldn't Have to Say Something For You to Do Your Job

Southern Orange County and Northern Rockland face the threat of more frequent forest fires, fueled by Climate Change. This weekend, some local governments demonstrated that they are not prepared.

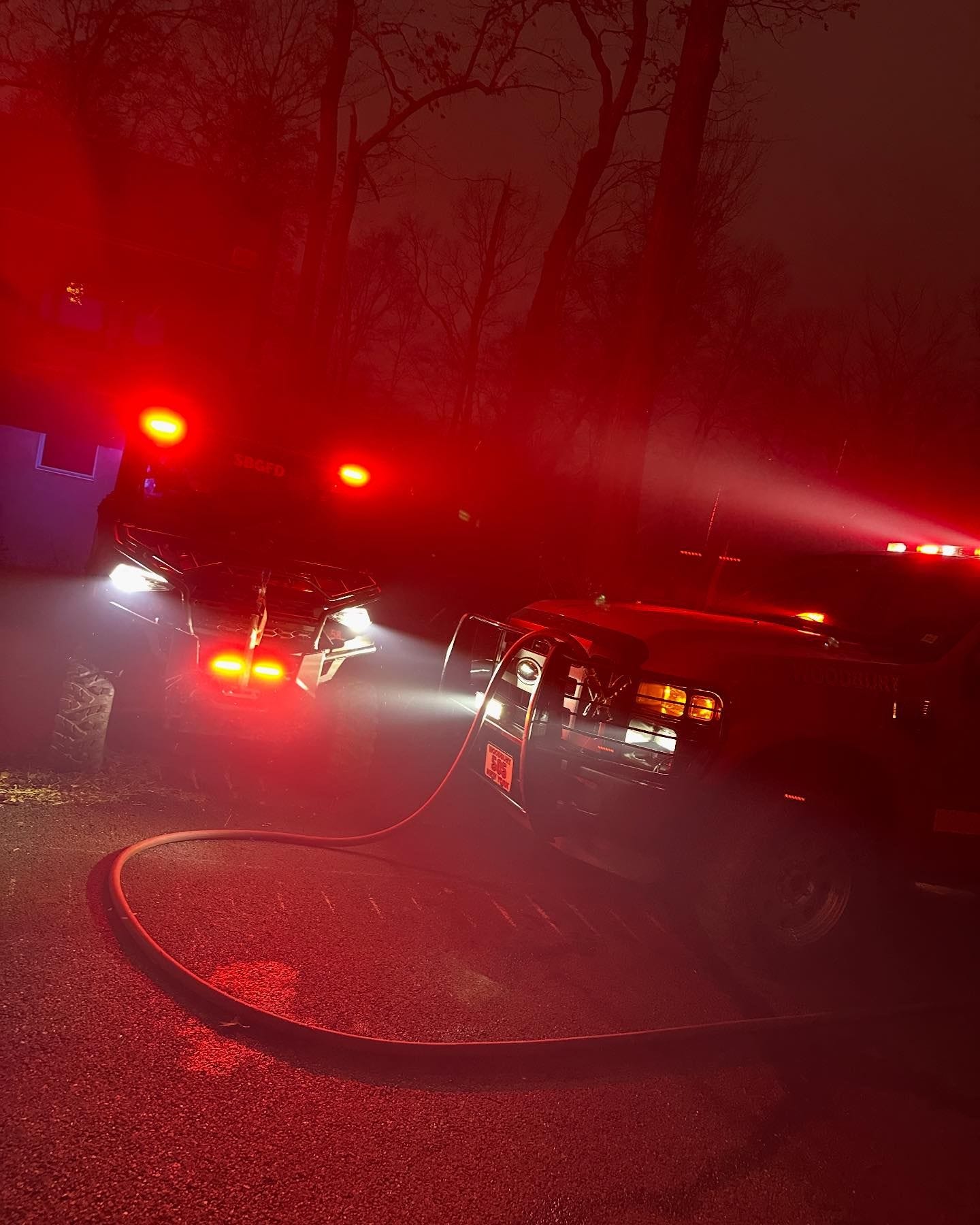

Above: A photo from the Woodbury Fire Department volunteers on-site at the Jennings Creek fire in Greenwood Lake.

Less than eight miles away in the Town of Monroe, Monroe has no emergency plan for its residents. The Town also provided no updates to residents throughout the weekend, despite the proximity of this fire and nearby brush fires on the Monroe/Tuxedo border.

Crooked Orange County Executive Steve Neuhaus and the BFL (Dorey Houle) were spotted by volunteer firefighters surveying the Jennings Creek fire on Saturday.

Dorey Houle intends to run for Monroe Town Supervisor next November with the blessing and support of State Senator James G. Skoufis.

(The proposed arrangement is that State Senator James Skoufis will support Dorey Houle in exchange for Dorey Houle not running against him, for a third consecutive time, for State Senator in 2026.

Neither Mrs. Houle nor Mr. Skoufis responded to requests for comment about this, but The Monroe Gazette was able to verify the proposed deal via sources close to both. The State Senator has a standing policy of not answering any inquiries from The Monroe Gazette because he’s a big baby who can’t handle criticism.)

Despite wanting to be Town of Monroe Supervisor — and currently having access to the Town of Monroe Facebook Page in her capacity as Town Councilwoman and Deputy Supervisor — The BFL, Dorey Houle, opted not to provide any updates to Town residents concerning the potential threat the neighboring fires posed to public safety this weekend.

(The B stands for Big. The L stands for Loser. You can figure out what the F stands for. The name comes from Mrs. Houle losing twice to Senator Skoufis in 2022 and 2024 for the New York State Senate Seat, and her poor behavior at Town of Monroe Board meetings due to her consecutive defeats. Here is the latest example of that.)

Instead of getting information from Mrs. Houle, area residents were dependent on a single, brave volunteer who provided real-time notifications on Facebook. Residents who were not aware of this brave volunteer’s work, or who wisely preferred NOT to get all their information entirely through Facebook, were left in the dark with no updates at all, potentially putting their lives in danger had this fire spread or any of the associated brush fires on the Monroe-Tuxedo border had done so.

Only after The Monroe Gazette posted about the lack of communication did the Town of Monroe send an email soliciting donations for the Greenwood Lake Fire Department. The email offered no other information to the public about the status of the fires or whether or not any of them posed a threat to the safety of the Town’s residents.

Above: Woodbury Fire Fighters battle the Jennings Creek fire. The Village of Woodbury was one of very few municipalities providing updates to its residents concerning the fire this weekend.

Back in May, I had a great discussion with Joshua Laird, the Executive Director of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission. Based on the findings of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, we discussed what climate change means for our region (Northern Rockland, Southern Orange County) in terms of forest fires and flooding.

All of Upstate New York will become increasingly under threat from forest fires like the Jennings Creek Fire because of the extended periods of hot, dry weather.

Climate Change and its impact on New York State is paradoxical.

On the one hand, we can expect plenty of heavy rain, but on the other, we can also expect long periods of hot, dry weather, like the one we’re experiencing right now.

The trick is figuring out how to store and utilize the excess rainwater when we get it and making sure that all current and future buildings in our region capture and make use of this water, while not wasting what we have.

All readers of The Monroe Gazette are urged to familiarize themselves with New York State’s Constitutional Amendment, known as The Green Amendment, which says: “Each person shall have a right to clean air and water and a healthful environment." This language will help in aiding future lawsuits against municipalities that violate it.

Thus far, few municipalities in our area have offered a strategic plan to better manage their water or to manage the new threat of frequent forest fires.

As we’ll cover later this week, many operate as if nothing is happening with the climate at all.

For example, the Village of Washingtonville continues to sell its “excess” water via Spindler Bulk Transit to neighboring South Blooming Grove, a village with its own well-documented water emergency.

Washingtonville does not have much “excess” water to offer, but the municipality is cash-strapped. So, it continues to sell the water to Spindler regardless of the long-term ramifications of not storing that “excess” water for events like the Jennings Creek fire and the current drought conditions.

Before we get into the Jennings Creek fire and the Town of Monroe’s total failure to inform its residents of its potential danger—that post is coming tomorrow—I want to rewind the clock to May and share the entirety of my interview with Mr. Laird.

In it, we discuss how the Palisades Interstate Park Commission is managing the increasing threat of forest fires due to Climate Change.

The following transcript has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity. All photos below are courtesy of the Woodbury Fire Department and were taken this weekend at the site of the Jennings Creek fire. Emphasis has been added to the transcript and appears in bold.

How Climate Change Impacts Harriman State Park and the Palisades Interstate Park system

B.J. Mendelson: To give you some context, what I'm looking to do is help explain how climate change is impacting people on a local level, so that they can kind of see and feel what's happening, as opposed to the more abstract discussion of it, obviously, you know, you mentioned the flooding, and I'm definitely very aware of that, so people are seeing some of the effects, but I'm trying to make it as localized as I can.

I want to use Harriman State Park, and I guess also the Palisades Interstate Park as well, to kind of explain what's going on.

So I wanted to speak with you first about the risk of forest fires in light of climate change within the parks, and then also about the flooding and the damage that it all has caused.

Joshua Laird, Executive Director Palisades Interstate Park Commission:

Sure, well, I mean, you know, in any climate change scenario, we're expecting to see more extremes on both ends. I think you know, as I noted in my email, overall, there is the prediction that the Northeast will see more precipitation over time than less, but we still expect to see periods of drought as well as periods of intense flooding, and we really need to be prepared for both.

So, yeah, I mean brush fires and forest fires in our region, and especially in Harriman State Park, are, you know, have been a real hazard for us in recent years.

Last year was a bit down, and this spring was down because we had such a wet spring. You know, fuel sources were pretty damp and we had a couple of fires, a handful of fires, but it was definitely down this year … it has an effect in several ways.

Drought increases the risk of fires. And we've seen that typically, in our park, they get caused by, sometimes by lightning. Certainly [we] have our share of illegal camping that goes on, people creating campfires and places they shouldn't.

We've had instances … Harriman State Park's electric network is primarily overhead. And you know, our forefathers, who created the park, elected to put a lot of that distribution system through the woods to keep it away from public roads. I've never seen any direct writing on this. The presumption then [was] that they were trying to reduce the visual impact of having these poles along the roadways.

But, you know, at this point in our history, we've got all these distribution lines through the woods, and so when trees come down, it's a constant battle to keep clearances so that lines don't come down with them. So we've had instances of a tree coming down and bringing down a power line and then sparks and ignites a fire. So there are a number of different causes when the ground is dry.

There is a both a, you know, a spring fire season where there is a lot of leaf litter on the ground from the prior fall that dries out and can dry out very quickly. And you know it's like fire starter all over the forest floor. You know that can be mitigated at times, because even though the surface is dry, if we've had a wet winter, we've had a proper winter with snow and rain on the ground. Below ground there may be enough dampness to prevent a surface fire from really spreading too much.

And then in the later in the summer and in the fall, we have another fire season, as things have dried out, if there's been, if there's a summertime drought. And then those fall storms begin to come in. That's when that risk in particular, of you know, of electric lines coming down in storms.

We have our own fire brigade in the Harriman State Park and in the Palisades region. They are our Park Forest Rangers. So these are a team within the region, and we're the only state park region in New York that has these Park Forest Rangers. They are attached to the State Park Police, so they have a law enforcement status, but their primary role is, they are our fire response team. They are our search and rescue team, you know, and there are emergency response teams.

So they are trained in fighting wildland fires. They're trained in first aid and in search and rescue techniques, so they are the first stop when a fire is detected. And, you know, we're beginning to get into things like drones, keeping an eye out for smoke plumes. We're just beginning to catch up.

We have a couple of trained drone pilots. At this point, we're really just beginning to create that program.

We have close relationships with local fire brigades. So after our Park Forest Rangers may be first to respond, we have the ability to call in the fire districts from neighboring communities, and they are excellent about responding, and have, over the years, developed good knowledge of the parks. So they know, depending on what location we're talking about, you know how to get there, where the water sources are, and what they'll need to do to help respond.

Beyond our forest rangers, [we] have a crew of park workers who had some training. We can call in, you know, as a collateral duty, who will come in and can fight fires as well.

So [if] we have a larger fire, beyond our forest rangers, we can call in other, other park staff, and, of course, our neighboring Park regions. Also, at times, they’ve sent staff over, and we've sent staff to them when needed. So there's a, there's a lot of cooperation that goes into scaling up and up or down for responding to fires.

B. J. Mendelson: That's great.

Joshua Laird: Yeah. We had a fire two years ago at Minnewaska Park preserve that was over 100 acres, and that, for us, is quite large. I mean, you know, when you think about the wildland fires out west on Park Service or Bureau of Land Management lands that are 10s of 1000s of acres or millions of acres, that's unheard of in this region.

Of course, we don't have the vast expanses of forest lands and grasslands the way they do out west. So there's not, as you know, it's not really as much a possibility. So because of all of the communities in the Northeast that maintain their own Fire departments, in many instances, volunteer fire departments, that is, there is a, as I say, a sort of a scalable level of response that's possible here that usually allows us to keep, brush fires down to a handful of acres, and it's been I, I think there haven't been a lot of notable incidents of fire spreading into and destroying real property assets. Getting into people's … stories of homes and communities that have been ravaged by fires in the way they have out west. So we're grateful.

Whether we're talking about drought or flood, it goes beyond the immediate impacts of the weather, fire, or flood in terms of how climate change is affecting the lives of our parks and people who live in the communities around us. It's affecting the health of our landscape.

One hears all the time about the latest, you know, pest or blight that's affecting our forests. You know, there was the spongy moth outbreak this year, there's the spotted lantern fly, the emerald ash borer, and all these different diseases. And as I say, blights and pests that are weakening our forests and eradicating, you know, habitat for native species. And threatening agricultural industries.

So the effects of climate change are profound and complex. It's not just the, you know, the big fires and floods. It's really hitting us where, where we live, and affecting industries and affecting recreation, including the recreation industry, of course, but you know, the agricultural industries, and, yeah, it's, it's really going to result in an entire change in our landscape, our natural landscapes, over the years ahead.

B.J. Mendelson: This goes back a little bit to the power lines that you mentioned that were put up initially. Is there, forgive my ignorance on this. Is there some master plan that the Parks Commission is following in order to, I guess, mitigate these effects as best they can?

Joshua Laird: Well, you know, it's challenging because it occurs on so many different levels.

We're doing a study in Harriman State Park because of the number of hazardous algal blooms we've had in recent years. And it's not just us. I mean, I think every region, every state park region in New York, has experienced the increased blooms that impact recreational swimming and boating and fishing and it's partly a function of of climate change, not strictly.

There are other factors from development and nutrient loading and things like that. But, you know, hot, dry weather tends to cause these blooms to occur as well and lower lake levels in times of drought when we're not getting that sort of natural you know, replenishment of water bodies.

We're looking right now at techniques that we're going to need to employ to reduce those blooms at Lake Welch in Harriman State Park right now, you know, we're looking at upgrades to our local wastewater treatment plant to reduce nutrient loading in the lake, but we have also been experimenting with these ultrasonic, solar powered ultrasonic devices in the water that are, I would, I guess I would say, somewhat experimental … But the concept is they're emitting these ultrasonic waves that are designed to disrupt the cells in the cyanobacteria that are the sort of the toxic product in these hazardous blooms.

They somehow are meant to send the cyanobacteria cells sinking, to the bottom of the lake where they die. They need to be at the surface, you know, sort of getting the sun in order to to thrive.

And so we're employing these devices right now. You can see them on the surface of the lake. There's, I think there … There are four of them in Lake Welch right now, and a couple of Lake Tiorati near the Tiorati beach. You can see them, sort of lying low in the water with solar panels on the top.

And they're clearly not completely Silver Bullets for dissolving it. But we did have a reduced number of halves last summer, which was the first whole summer we employed them. And so we're hoping that over the course of … some time and data collection, these devices will show to be helpful.

Under the Governor's Executive Order 22 we have a host of of initiatives designed to reduce our own carbon footprint and reduce our power consumption. That's not so much a localized … it's part of a grand effort to deal with climate change.

Providing EV charging stations and and solar panels is not, you know, targeted at mitigating climate change in our local parks but that hopefully will contribute to the bigger, bigger battle to to stave off or reduce the acceleration of climate change.

And those are, you know, those are the primary ways in which we have a variety through our Natural Resources Division, where we're looking at specific flora and fauna that are in peril through climate change as well as other other things, development and so forth, and we're trying to be strategic about focusing our resources where they'll do the most good, because you can't win every battle, and you're not going to eradicate every weed, or every species of weed.

So you try and get at the ones, the battles that are winnable, and you look at things like, like tidal wetlands and big initiatives with State DEC yet, you know, Iona Marsh off Bear Mountain, as well as Piermont Marsh further down near Tallman Mountain State Park where we're trying to preserve native marshlands, which are one way of helping to mitigate sea level rise. Or at least flooding there that results from sea level rise by creating these natural barriers that can help absorb flooding and reduce the, you know, the impacts of storm weather blowing in.

We're also looking at all of our ancient infrastructure, so you know, our parks here in the Palisades, like Harriman and, you know, have a really impressive network of drainage structures meant to channel water to help. With the historic intent of keeping water away from, from recreation areas, from, you know, feeding swimming areas, from keeping trails from washing out. But aside from the pure age of those structures, they're also designed for climate patterns of a century ago.

In many instances [they’re] overwhelmed by not just the frequency of storms, but the severity of storms. So you know, a great example of that is Tallman Mountain State Park in Rockland County, where we've now had, you know, a couple of major washouts from storms that just overwhelmed the parks drainage infrastructures, just, you know, beyond the capacity of water they were designed to hold.

And our pool at Tallman Mountain has been (laughs) been flooded out with mud. And, you know, rock slides a couple of times now. So we have a design on the boards that will do a combination of increasing the capacity of our drainage structures, barging them, and also, you know, making an effort to redirect storm runoff away from some of our critical facilities. So we hope that will be, you know, say we're just completing the design, and that will become a priority for us, implementing that over the next couple of years. And then, of course, last year, at Bear Mountain and Harriman, we had this major flood event in July that closed Bear Mountain entirely for six weeks. And basically it [the storm] was a bull's eye at Bear's Mountain. And then it also hit the northern end of Harriman State Park. And you know, in response to that storm the governor's office funded millions of dollars in repairs.

And indeed, with each repair we've tried to create a more resilient, sort of condition then, what we started off with before the storm.

Those millions, I'm just talking about repairs on the park, you know, DOT [Department of Transportation] got, and all of our local roads in the Palisades Parkway, got a huge amount of damage around the area, and they've also been investing tons of money to help deal with those issues.

So, you know, enlarging culverts, drainage swales, redirecting runoff. That's been a strange byproduct of the severe storm events that I think we're just beginning to wrap our heads around, which is that it's not just a severe rainstorm that produces a higher volume of water and, therefore, more flooding. We're [also] seeing flooding in places that have never flooded before.

I think these, you know, just the repeated number of storms is carving out new pathways, or storm runoff, [water] trying to get away, trying to find its way downhill and that that is creating this new sort of more permanent runoff channels.

So, you know, again, we're, we're beginning to see, even [during] less severe storm events, water beginning to show up in places where we didn't see it in the past. And we're going to have to … Water is always trying to find a way down, needless to say, that gets blocked in one place, it's going to try and find another place. And so we're, we're beginning to experience the ramifications of that as well.

B.J. Mendelson: let me ask you a little bit about U.S. Route 6 and Bear Mountain. I'm sorry, not Bear Mountain. I mean the US 6 traffic circle [on Long Mountain Parkway], because I know, for my readers I focus primarily on Southern Orange County, and so that is one of the main arteries to get to New York City. So I know that it was heavily damaged, and I know you touched on it a little bit, but I'd love to hear a bit more about what happened. And then, you know, do you expect that this is going to be something commuters might experience more in the future?

Is there a possibility that this, this is might become routine “of okay, well, we have to shut down this traffic circle?"

Joshua Laird: Well, hopefully not routine. I mean, so again, with repairs that we've made and, and DOT, you know, particularly, it's, you know, DOT that handle repairs at the Circle and on the parkway and on Route six. And along the shoulders of those roads, you can, it's quite visible there. [The repairs.]

As you drive by those areas that took the worst damage that the DOT has come in and not just, you know, reestablish those drainage … but they've reinforced them with rock and I think better enabled them to withstand the force of rushing water after the severe storm event.

So I think they have, and we've done the same on our roads, along Seven Lakes Drive, and so forth.

I think we have made ourselves more resilient. Not impervious for sure. So when these super strong events come by we're going to continue to be vulnerable, and we're going to continue to respond as best we can. And you know, each time we will.

The goal is to come back. You know, better and stronger than before, but keeping up with a climate that's changing quickly, and really only beginning to … People have been talking about severe weather for a while, but now we're really, really beginning to experience it.

We had, I don't know if you know, we had a, we had a microburst over Harriman last week.

B.J: Yes,

Joshua Laird: … And, you know, it did. It did an amazing amount of damage, localized, fortunately, but, you know, trees just, not just uprooted, but, like, snap off mid-trunk. I mean, I've never, I've never seen anything quite like this, which you just see, you know, a tree in full canopy just snapped off.

And you know, we're trying to find that balance right? We're trying to preserve these environments and steward our forests. And, you know, the solution can't be, well, we're just cut down every tree, and then we won't have any more trees fall down. But, you know (laughs) but we're still going to have to deal with these storms coming through.

And there's, there's no way I could think of to really mitigate that kind of super severe Microburst that is just enough to snap a, you know, a, you know, an oak tree in half, Right?

B.J. Mendelson: Yeah, it's definitely, well, terrifying, in a certain respect.

My last question for you then would be, you know, look, going into the summer —we just had this microburst—are there any plans or projections or things that you're keeping an eye on as we start to approach the hot weather?

Joshua Laird: um, I mean, I, you know, I think, again, it's sort of an exacerbation of things that we've always been aware of, you know, it's, I mean, brush fires and forest fires are not new to climate change, but they're happening with more frequency.

So we're bracing ourselves by making sure we have our eyes open and that we're aware of the conditions or being more vigilant about, you know, communicating fire risk warnings to the public.

We have, in addition to our Park Forest Rangers, now State Parks has sort of a growing seasonal Ranger program … I think something like Park safety rangers who are playing a role. In addition to helping manage people to focus on that public education component, because we really need the public to help us as well by being smarter about and more attuned to the risk of that stray match. Or what happens if you create your own little fire pit and the worst thing is to then to do that and then walk away from it.

So those are all part of our kit at Parks. The power issue that I mentioned before is tricky. Harriman State Park itself is so rocky it's sort of a landscape perched on these rock outcropping that burying lines below ground, which might be, you know, the ideal, is challenging, because you couldn't do that without blasting through the rock. And it's not really a possibility in a lot of locations.

So we're stuck with those overhead power lines until we can get to a place where maybe there are ways to get off the grid and not have those lines. But you know, until then, we just do.

It's a combination of the ability to respond in emergencies and just baseline levels of maintenance and being able to stay on top of trees that are in poor health. And you know, in locations where they pose a danger, or could potentially pose a danger if they fall. Look at the condition of our power lines and our poles and make sure they're in good shape. And working with the local utilities and their efforts to maintain power line corridors and to prune trees within X distance of their pole lines, and so all those, all those things, are a part of the sort of the toolkit that we use

B.J. Mendelson: Is there anything that I should have asked that I didn't that you wanted to touch on?

Joshua Laird: I think I pretty much covered everything I intended to. And, you know, I think it's important to talk about not just the hazards of, things falling or bursting into sparks during a storm … But the sort of the fundamental change to our landscape and all that that's going to mean. The sort of domino effect of these blights and pests coming through. And what that's going to mean over time for our resiliency is, I think, something we're still trying to understand.

***

The Monroe Gazette would like to extend its condolences to the family of NYS Parks employee Dariel Vasquez. Dariel was 18 years old and part of the NYS Parks Wildland Fire Crew, assisting in managing the Jennings Creek fire. Members of Dariel’s family have set up a GoFundMe that you can find here.

thank you for this important article.